Designer: Masato Uesugi

Publisher: I Was Game

Players: 2 or 4

Times Played: 21 times

I’m writing this as a “review” of Ortrick, but there are a few things you should know before we get started. It is scheduled today because I helped license the game for Allplay (boardgametables.com) and they are launching it on Kickstarter on Tuesday, under the new name and theme, Lunar. I will indirectly financially benefit if you back it.

I love trick-taking games. I think my love for them is rooted in their shared heritage and vocabulary – each being a new interpretation on some sort of ancestral archetype where we each played a card in order, had to play the same suit as the first person, and then some other things happened. I like thinking about the different directions designers push the genre in – and made a big spreadsheet (constantly in progress), so I can ask it questions “are there any ‘may follow’ games with bidding?” or “what other games are there where you can only win a fixed number of tricks?”

The history is important to me. There’s only a certain few titles which will rise to the top and garner much sales or hype, here, in a dusty corner of the larger hobby’s zeitgeist, but I don’t want other games which do interesting things to be forgotten.

Naturally, though, there are important aspects which I can’t capture in a spreadsheet. How does the game feel? What is the experience of playing it like? It is in this question that I think I found something special which connects the trick-taking games I love – and which Ortrick embodies.

In short, the best trick-taking games are those in which the outcome of the hand isn’t known until the final trick. That is, not the games where only the final trick has value (such as the Cucumber family), but those where you won’t know the full resolution until the end. Maybe it is a bidding game – you need to win 2 tricks and have only won 1 so far. Those can also have the inverse – as once you win 3 tricks, the drama starts to leak out of the remainder of the play.

Maybe it’s in who will capture a certain card – and until that card is played, the game hangs in the balance. If it’s played early, the rest of the hand is less engaging.

Hands in some games can be over before play even begins. You can’t inject any drama into a poor hand in Tichu or Euchre, so those games try to make it up in volume of hands.

I think this feeling is most easily observed in games of The Crew – where you have the anticipation of completing your goals, but for some combinations, once you do…there’s an awkward pause until somebody chimes in “so…do we need to play the rest of the tricks?”

Ortrick isn’t unique in nailing this feeling – I think many modern trick-takers get this right. But, well, let’s get into it more after I explain how it plays.

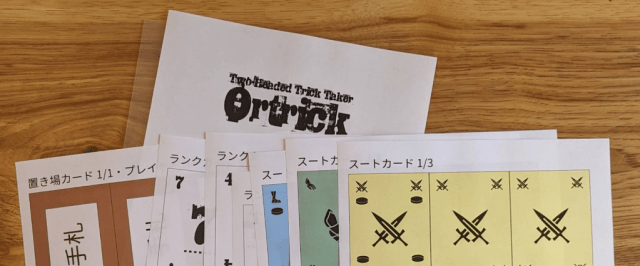

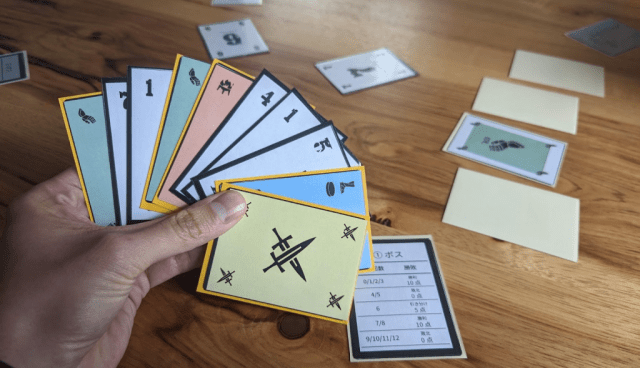

Building on the foundations of games like Transportation Tricks and Dois, Ortrick is a game in which the suits and ranks are separated on different cards. To play a “blue 2”, it will need to be two cards – a “blue” card and a “2” card. For the partnership game, this means you may be playing “4” while your partner will play “red”; together, you’ve played a red 4.

Building on the foundation of Fox in the Forest, if your team is scoring a lot of points, the other team is probably not scoring many. Each hand in Ortrick is 12 tricks. If one team wins 0 to 3 tricks, they earn 10 points, and the other team gets…nothing. If that team makes it to 4 or 5 tricks, things reverse, and the team which won 4 or 5 tricks gets nothing…and the other team gets 10 points.

Ortrick also has certain cards you want to capture which will be worth a point regardless of how many tricks you win. In total, 17 points are available each hand – 10 from winning tricks and 7 from capturing certain cards. This makes the two “landing spaces” for how many tricks you want to win interesting. If your team tries to win 0 to 3 tricks, you have a 4 trick variance to get it right; while winning 7 or 8 only gives you 2 possible results – but winning those extra tricks means you probably are getting more of the point cards. (…spoilers!)

So that’s the basic structure, but there are some finer points to touch on – if our team wins a trick, who leads next? Neither of us played the winning card, as we both played half of it! Ortrick uses the unique feature of a fixed team lead. If we’re partners, I will always lead tricks we win in this hand, and those roles will rotate after each hand. This has a few interesting corollaries, such as (roughly) fixed seating in each trick – for this hand, I’ll be 1st or 4th and you’ll be 2nd or 3rd. This informs which cards I pass at the start of the hand and how I’ll lead. I love that each position has a unique feel.

The setup of the game ensures that we each start with half suit cards and half number cards, and they have distinct backs. If the start player in the trick leads a number card, what is the lead suit? That’s not a koan, there’s an answer, and in this case, and all the others (like the turn order discussion above), the game chooses the simplest resolution: the first suit played is the lead suit.

This means the leader of your team (the “boss” in the original game) has some extra responsibilities around managing the balance of the suits. You need to think ahead to the end of the game – if you run short on suits and are playing numbers, can you force the other team to play a suit first – increasing the odds that they win the trick (but did you pass your partner any cards of the trump suit? Did they play them?) If you are short on suits, it also means your partner has an abundance. Maybe you want to maintain a balance; maybe you don’t. These are interesting decisions.

Continuing backwards in my explanation, after you are dealt your hand of cards, you’ll pass two of each type to your partner. The game doesn’t offer you any overt forms of communication outside of these card passes and your card plays. Some of the card play moments will have an unambiguous meaning – but to your opponent as well. If your partner will be the last to play to a trick and seems to play a gratuitously high or low card – are they signaling that they want to land on the lower platform (winning 0 to 3 tricks) or the higher one (7 to 8)? There are more subtle ways to communicate through the card pass and leveraging your observations about your partner’s play from what you know you passed them.

There’s also some decisions around the trump suit mechanic. After the pass, the “boss” of the first team chooses one suit not to be trump for the round. Then, the “boss” of the other team makes the same choice, and then the minion of the first team. That leaves one suit and it becomes trump.

That also leaves the minion of the second team to do…nothing? Well, as I’ve started saying after I finish the rules teach to any game: “these are the rules.” According to the designer, they believe that this last player – who will be going third or fourth in all tricks – has enough influence on the outcome of the hand, that they don’t need the extra lever. I think I agree.

There are also two player rules! (And they are also great!) It uses a “strawman” type dummy hand, as in games like The Crew’s 2P rules. Half of the suits and half of the numbers are undealt and form two decks. For each trick, there are three of these cards face up – and each player will play one card from their hand and one of these face up ones. The face up cards are both players’ partners. It’s clever and fulfilling.

This is a game full of “stand up” moments. Well, specifically, at the end of a hand. The designer has done a brilliant job of tying all of our fates together. You will have hands where both teams win 6 tricks, and the scoring advantage comes down to who won more of the point cards. But let’s rewind that one card play.

The score is: your team 5 tricks, my team 6. If you win this trick, you’ve gone up 5 points, and we split them. If I win this trick, we go up 5 points, and come out 10 to 0. That’s a lot riding on this trick.

I play a 2, your boss plays red, my partner plays red…and the entire hand has come down to your card play. That is, it hasn’t just ensured that the hand is dramatic because of the last trick, but many times it has assuredly put that pressure on the _last card_ played to the last trick. Our team’s score is generally the inverse of your team’s score. My partner’s score is my score. Neither of the cards played to a trick coalesce until the last person’s card is put into play. Q.E.D.

(There’s also a follow-up observation that the structure of the rules has tied every player’s fate to the last card play! In our earlier example, you bid 2 and need to win one more trick…but maybe the other players are done with interesting play for the round. Here, if one player’s outcome is undetermined, everyone’s is. Brilliant.)

Sure, there are times when it won’t be this dramatic, and I hope I haven’t oversold it, but most of the time…it is like this! And that’s why it’s so full of stand up moments. Every “win” of a hand is a walk-off win. That is, a sports analogy. The game is tied in the bottom of the 9th inning… We’re in double sudden death overtime…. And whatever the equivalent is in soccer… The next person to do the awesome scoring thing will win it all.

Now imagine a trick-taking game that has bottled all of that into _every hand_. (Geez, I hope I’m not overselling it.) I also fear this level of analysis of why I adore this game is like explaining why a joke is funny.

Anyway, as always, I hope you like it. 💛

best,

JN

Ratings from the Opinionated Gamers

I love it! James Nathan

I like it. John P, Eric M

Neutral.

Not for me…

Great review. I can’t wait to get a copy of Lunar!

Your enthusiasm for trick-taking games (and games in general) comes thru in spades and I loved the write-up. Having been a part of one of those standup moments, I agree that this one is a winner!